By Christopher Elliott

When it comes to new travel fees, the sky’s the limit. Or, in Liz Pollock’s case, the fourth floor of her hotel. Pollock recently checked out of the DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Golf Resort Palm Springs Area in Cathedral City, Calif., and discovered a mysterious fee on her hotel bill: a “top-floor” surcharge of $7 per night.

“I didn’t request a room on the fourth floor,” says Pollock, a benefits manager for a clothing company in San Francisco. “And I didn’t find out about the fee until after I’d checked out.”

Here’s the thing about the top-floor rooms at the DoubleTree: They’re more or less the same as the rooms on the third floor, except that they “allow for the best view of the surrounding area,” according to Robert Hatfield, the hotel’s director of sales.

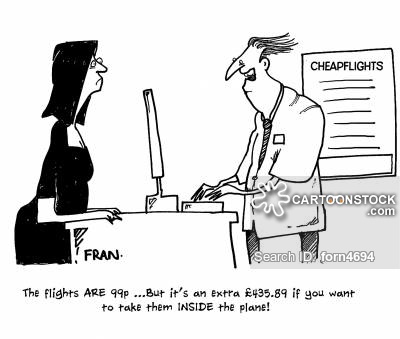

A “top-floor” charge? Why not? To squeeze a little more revenue from their guests, travel companies are getting creative. The only way to fight back is to become just as creative about fighting them.

“Hidden fees are taking advantage of consumers across the country,” says Bret Bonnet, co-founder of People for Honest Pricing, an organization that lobbies for fair pricing and certifies businesses that practice honest pricing. “While they’re definitely not a new phenomenon, they seem to be getting worse.”

For Pollock, who was in Cathedral City for just a few days, the “top-floor” fee was particularly annoying.

The DoubleTree had already billed her a mandatory $25-per-night resort fee, which covered on-site self-parking and Internet “even though Hilton Honors members are supposed to receive free Internet if they book through Hilton.” But it really topped itself with the top-floor charge. Hilton hadn’t warned her about the fee before the reservation and didn’t inform her about it until long after she’d left the property.

That’s not how it’s supposed to work, Hatfield says.

“A guest will receive a pre-arrival email with the upgrade options available to them and what the additional charge for those items are,” he explains. “Once the guest chooses the upgrade option, the resort is notified. Once we make the upgrades, the guest is then notified via email. This all happens before arrival.”

Pollock solved the mystery when she asked her husband about the charge.

“Apparently, sometime after the reservation was made back in October, he went on the Hilton website and noticed there was an ‘upgrade’ option at the bottom of the page. He clicked ‘yes’ to upgrade to the fourth floor,” she says, without noticing that he would incur an additional charge. “He’s a huge golfer and wanted as big a view of the golf course as he could get.”

Sometimes, old fees hide under new names. For example, the $20-a-day resort fee is called a “guest amenity fee” at the Le Meridien Delfina Santa Monica. In San Francisco, you’re more likely to find an “urban fee” or “facility fee” on your bill. It’s all the same thing — just don’t use the “R” word.

Not to be outdone, American Airlines and United Airlines last year quietly implemented “gate handling” and “gate service” fees of $25 to check your bag when you board if there’s no room on the plane for your carry-on and you’re flying on a “basic” economy class ticket. Wouldn’t want to call these luggage fees, since passengers will do almost anything to avoid those.

Michael McCall, a professor of hospitality business at Michigan State University, says travelers knew about the old fees, thanks to press accounts and word of mouth. The workaround: rename them. “The concept often works,” he says.

If you’re on a cruise, look out for one of the newest “gotchas” — if one person buys an alcohol package, the cruise line requires every adult in the same cabin to buy one.

For example, Royal Caribbean’s “deluxe drink package” lets you choose between unlimited cocktails, beer, wine, nonalcoholic beverages, premium coffee, tea and bottled water, for a flat fee of $55 per person, per day. “So if a husband wants to get a package because he likes to have drinks on the ship and a wife doesn’t want a drop of alcohol, too bad,” says Tanner Callais, founder of the cruise site Cruzely.com.

Fees are a big deal in travel, at least to the companies that charge them.

Domestic airlines collected $4.6 billion in baggage fees in 2016, the last year for which numbers are available. Hotels collected $2.7 billion in fees last year. To extract them from guests, travel companies often fail to adequately disclose them or don’t reveal them until you receive a bill, which can retroactively take the fun out of any trip.

What’s the antidote to these fees? Assume you’ll get a creative surcharge the next time you travel.

Use all of the proven tactics and look for new ways around them. Those include reading the fine print on every purchase, questioning any fees you don’t recognize and taking aggressive measures to remove them from your bill.

“You should always demand to know what exactly you’re paying for,” Bonnet says. “If it seems fraudulent, sometimes even refusing to pay the fee is warranted.”

If you can prove a hotel or airline failed to disclose a mandatory fee, you have a reasonably good case. I’ve seen credit cards side with consumers when they disputed the charges.

But perhaps the best way to avoid creative new fees is to never do business with an airline, car rental company, hotel, or cruise line that imposes them.

If you encounter a problematic fee, tell everyone. If you see that a company charges a creative fee, avoid it. If enough travelers do the same, these new junk fees may end up in the trash.

Christopher Elliott’s latest book is “How To Be The World’s Smartest Traveler” (National Geographic). This column originally appeared in the Washington Post.

Get Social