The numbers are neither startling nor new. Greater than one in three (39.8 percent) of Americans are obese, according to the CDC. That means nearly 100 million US adults are officially overweight and may be flying soon in a seat near you. Or you may be one of the many flyers these days who has to fit into a shrinking airline seat and manage yoga maneuvers to use the airline lavatory on a five-hour flight from New York to Los Angeles.

Being that passenger, or the passenger next to that passenger, can become an uncomfortable predicament, yet there are few solutions in the offing that offer even the perception of management for this ongoing conundrum.

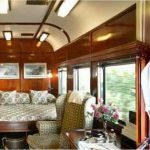

The average American man weighs 15 pounds more than he did 20 years ago, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The average American woman weighs 16.2 pounds more. But the average seat pitch, a rough measure of legroom, has dropped from 35 inches in the 1970s to about 31 inches today. And the average width has shriveled from 18 inches to about 16.5 inches. Airline bathrooms are also seeing similar shrinkage. U.S. carriers are installing bathroom spaces that are at least three inches smaller than they were earlier in the decade and for many flyers, those three inches matter.

Airlines need to be more sensitive to passenger discomforts and territorial seat skirmishes, says Christopher Elliott, a consumer advocate, journalist and co-founder of the advocacy group Travelers United.

Oversize airline passengers fall into two broad categories, he says. Some travelers can’t fit into the seats because of their hip size. Others are too tall to contort into an economy-class seat with limited legroom. The ones that generate the most complaints, perhaps unfairly, are the ones who spread into the next seat.

That’s what happened to 73-year-old Sam Cristol, says Elliott. He found himself seated next to a 6-foot-7, 500-pound passenger on a 5+-hour JetBlue flight from Fort Lauderdale to San Francisco.

“He looked like an NFL lineman,” Cristol told Elliott. The food broker from Lake Worth, Florida added, “he took up half my seat. My other half was in the aisle while I had to hold on to the seat in front of me.”

Cristol complained to JetBlue, which apologized for the inconvenience and the airline offered a $100 voucher to both him and the lineman.

Crewmembers usually try to fix these onboard confrontations before takeoff. For example, a flight attendant would have tried to re-seat a passenger like Cristol. But unfortunately, it was a completely full flight. He also might have asked to trade seats with a smaller passenger, but that wasn’t an option either.

So, beyond the usual advice – change seats, try to persuade a smaller passenger to take your place, beg for an upgrade – what do you do?

A little kindness would probably take you a long way, said Casey Gardonio-Foat, a small business owner from St. Louis, in an interview with Elliott.

“Have empathy for the larger person,” she said. “Remember, they are likely more uncomfortable than you are. That’s because of shrinking airline seats and because of bias and routinely awful treatment of larger people in American society.”

Suzanne Dixon, a dietitian from Portland, Oregon, agrees that being nice can make the trip more survivable, according to Elliott.

“When I’m seated next to a large passenger, I greet them with a smile,” she said. “No matter how much of a squeeze, a positive and nonjudgmental attitude is important.”

A polite request can help, too. On Stacy Caprio’s last flight, her seatmate took over her armrest and encroached into her personal space. “I asked him, ‘Could we please each keep our arms inside our own seats?’ ” Caprio, who works for a Canadian coupon website, told Elliott. “He grunted but then mostly complied which made the flight much more pleasant for me.”

Ken Friedlander was so concerned about passengers who spill into someone else’s space that he invented something to fix it. It’s a partition called Create-A-Space (createaspace.net, $39) that pushes up against your armrest, clearly delineating your personal room.

“I have found that coming prepared with something to help share the armrest really makes a difference,” he told Elliott. “The airlines have forced me to make this a part of good travel planning.”

Jen Lowe, Elliott says,” shared one of the cleverest techniques I’ve heard, although it’s not necessarily one I would endorse. She told me the story of a ‘super-intrusive’ seatmate on a recent flight who refused to move.”

Lowe, a swimsuit designer from San Diego, described a seatmate who was rude and unapologetic about physically taking up room in Lowe’s seat space. Halfway through the uncomfortable flight, the cabin turned cold, however, and Lowe had an idea.

“I just snuggled up to her and put my head on her cuddly shoulder,” she said. “It’s amazing how fast she was suddenly able to retract into her own seat – like, completely.”

In a recent incident involving Delta, Amber Manjee of Chattanooga, Tenn., was bumped to the back of the plane because of her weight. She had landed in an exit row seat and requested a seatbelt extender. But the next thing she knew, the flight attendant was loudly remonstrating that she had to move because of her weight, which would present safety issues in the exit row the event of an emergency evacuation. Shamed and humiliated, she moved accordingly and then took up her case with Delta through social media, eventually receiving a $500 voucher for her troubles.

Several airlines do have policies in place for dealing with the seat/size problem. Thai Airways, for instance, only recently put in a policy that effectively bans passengers with waists bigger than 56 inches from flying in the business class cabin of its Boeing 787-9 “Dreamliner” fleet. The policy redounds to safety issues put in place with the installation of airbags that are now part of the business cabin seat to prevent the passenger’s head from impact in the event of sudden deceleration.

Southwest Airlines encourages passengers to proactively purchase an extra seat if they will be extending their body beyond the armrest. Those passengers may be eligible for a refund of for the additional seating after travel. But the rules are still grey: Customers of size who prefer not to purchase an additional seat in advance have the option of purchasing just one seat and then discussing their seating needs with the Customer Service Agent at their departure gate. If it is determined that a second (or third) seat is needed, they will be accommodated with a complimentary additional seat.”

The issue of passenger weight surfaced in 2003 when a commuter plane crashed on takeoff from Charlotte, North Carolina, because of excess weight that tumbled into a maintenance error. The FAA was forced to increase the estimated weight per passenger by 10 pounds (at that time, likely more now), including 20 pounds of carry-on luggage.

In 2004, the Centers of Disease Control looked at the effects of obesity on the airline industry, calculating that if the average weight of an American had increased by 10 pounds in the 1990s that was a $275 million cost to the airlines for fuel in 2000.

Meanwhile, a flurry of lawsuits filed during these years by heavier passengers — and by those who complain about large passengers encroaching on their space – have resulted in rulings that favor the airlines.

For the overweight flyer, options beyond upgrading one’s seat or purchasing an extra seat, are limited as well. Expecting airlines to adjust their seat designs to an ever-widening average girth is probably not the way to go, especially in an era of ever-disappearing national industry regulations.

Addressing this problem for the adjacent passenger, Elliott suggests:

- Fly later. If you’re seated next to someone who can’t fit into one seat and your schedule is flexible, ask a flight attendant if you can take the next flight. If there’s room on the next plane, you might be better off traveling later.

- Know your legal rights. Unfortunately, you don’t really have that many. The contract of carriage, the legal contract between you and the airline, does not say you have a right to a full seat. Generally, the crew’s attitude is that if you can sit in the seat and use your seat belt, you’re good to go.

- Know what to expect when you complain. As a practical matter, airlines will apologize and maybe offer a voucher for your discomfort. Discreetly take pictures of the incursion and send them with your complaint. If the airline doesn’t respond appropriately, consider asking a third party for help with your case, such as a consumer advocate, or post your pictures on social media.

Get Social