Story and Photos by Susan McKee

Story and Photos by Susan McKee

Water is the reason for Venice. In prehistoric times, fishermen settled on the 118 small islands in the lagoon at the northwest corner of the Adriatic to take advantage of easy access to the sea’s bounty.

Then, in about the fifth century, barbarians from the north invaded the Italian peninsula. Anxious to avoid the marauders, mainlanders fled for refuge to the islands, protected by water from warriors on horseback.

Venice was born from this combination of forces: merchants and businessmen of the mainland joined the seafaring locals.

Soon, the city-state was growing exceedingly wealthy, trading local wares up and down the Adriatic and into the Mediterranean as well as bringing back exotic cargo from around the world.

It’s these centuries of trading success for Venice that makes it a “must see” for tourists. Under the unique governmental style of the doge — an elected-for-life leader — the city-state prospered for more than a thousand years.

Its sailors brought back priceless artifacts from across the known world, including the bones of St. Mark (taken from Alexandria in the 9th century) and the Triumphal Quadriga– now atop St. Mark’s Basilica (brought back from Constantinople about 1204).

The fabulous wealth of its citizens attracted artists, sculptors, musicians, architects – and a population that at one time exceeded that of London and Paris combined gave birth to an eclectic culture.

Tourists arrived in droves — and still do.

The canals of Venice aren’t the straight-shot transportation routes of canals in the northeastern United States. They’re organic waterways, snaking between the islands. Even the Grand Canal takes a sinuous route through Venice.

Streets – pedestrian only — are no better than the canals, as they follow the contours of the ancient islands as well. What seems like a straight shot across from, say, Piazza San Marco to the Rialto Bridge becomes an exercise in meandering.

Look up when you’re walking in Venice: there are directional arrows on the sides of buildings where streets intersect.

It’s often recommended that tourists begin their walks at the Piazza San Marco. This is, of course, the most famous spot in town: here are the basilica of St. Mark, the campanile and the Doge’s Palace.

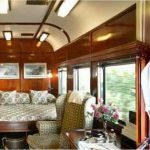

In the warmer months, this is where you’ll find the “dueling” orchestras of Caffè Florian (which opened in 1720) and Caffè Quadri (dating to 1638) facing off across the square as tourists and locals sit and sip their coffee at the outside tables.

In addition to the ubiquitous pigeons and souvenir vendors, the Piazza is laced with raised wooden walkways: when the tide is high, water bubbles up through the paving stones of the plaza, and washes over the walkway along the Grand Canal. These “temporary” walkways keep pedestrians out of the water.

Although I hit some of the high spots when I was in Venice, my favorite time in the city was spent just wandering. The shops offer everything from exquisite Murano glass to mass-produced masks.

Carnevale, of course, is Venice’s signature holiday. For the fortnight leading up to Ash Wednesday, the partying is nonstop. Next year’s dates are February 15 through March 4.

The rest of the year, it’s obvious that a mask is the signature souvenir of Venice. There are hundreds of vendors hawking the most awful imported schlock, but you can find shops and kiosks selling the plain, white papier-mâché version – purists buy these and fashion their own disguises.

I bought my souvenir mask in the shape of a mottled gold and green leaf at La Bottega dei Mascareri, near the northern (market) end of the Rialto Bridge. In this tiny studio/shop brothers Sergio and Massimo Boldrin hand-fashion the most amazing masks.

More information:

La Bottega dei Mascareri

Museum at St. Mark’s Basilica

More stories by Susan Mckee:

Savoring Vienna, One Sip at a Time

Albuquerque: Beauty and Breadth Beyond “Breaking Bad”

Learning to Sail in the Caribbean

Day by Day Up the Coast in Norway

Get Social