By Susan McKee

Slurp, slosh, spit, repeat. I watched Abir Goyal sample his way through a hundred different lots of tea in the broker’s office in Guwahati, India the largest city in Assam in northeastern India . This was his second taste test for the batch. The first was steeped with boiling water. This go-round added milk to the brewed tea, just as it would be drunk by the majority of tea drinkers in India.

He was tasting dust—the lowest quality of broken tea leaves that look like powder. Goyal said that it’s very popular in the south of India because it brews many more cups per kilo than the pricier leaf tea. He said it’s also used in tea bags.

Just like wine tasters, Goyal doesn’t actually swallow what he’s tasting; he just swirls it in his mouth for a bit. Tasting notes are dictated to the clerk following him down the line of teas identified only by number. “Thin,” he’d say. Or “thick” or “smooth,” or other succinct adjectives. The vocabulary, too, reminded me of wine tasting. Goyal assessed the weight and quality of the tea on his tongue, just like an experienced sommelier, checking for burnt, harsh or coarse overtones. “Malty” is sought after in Assamese teas, “metallic” is not. “Full-bodied” is the top designation, the target combination of strength and color.

He also looked closely at the unbrewed tea leaves next to the prepared cup, checking to see if it was well-picked and clean.

Goyal, who is a senior executive with Carritt Moran & Company, is charged with providing guidance for his company’s purchasing agents. Based on his tasting notes, they head to the tea auction in Guwahati and bid for the lots. Carritt Moran, founded in 1877, is the second-largest firm of tea auctioneers in the world, handling about one-fourth of the teas sold through the Indian auction system.

I had spent the morning at the Gauhati Tea Auction Center, watching both the live auction and the subsequent electronic auction. Assam—the province of which Guwahati (also called Gauhati) is the capital—grows most of the tea exported by India. Some 20 percent of Indian tea passes through this auction house. Watching the auction itself was mesmerizing. I had no idea what made one lot of tea worth more than another, but men such as Goyal certainly did.

I was staying with friends, originally from Darjeeling, who’d moved to Assam several years ago. Like many in Guwahati, they invested in a tea plantation, which is called a tea garden here. But they hadn’t visited their property in months; the region had become too dangerous.

The entire north-east section of India had been off-limits to foreigners for decades because of an ongoing guerrilla uprising against the central government. Although things had quieted down enough to lift the tourism prohibition, out in the distant reaches of the province things were still a little bit dicey. My friends said they’d ransomed their tea garden manager twice now, that keeping good staff was a problem when kidnapping was a routine occurrence.

I didn’t see any trouble in the tea plantation I visited, however. The Brahmaputra River is bordered by more than a half a million acres of lush green tea gardens growing in the rich alluvial soil. The total production of tea in Assam approaches one million pounds per year.

The tea gardens themselves are beautiful. The emerald green of the waist-high camellia sinensis bushes seems to glow from within.

The best tea is picked by hand, and (literally) whole villages of migrant workers are imported to do the specialized work. First comes withering, when the freshly picked green leaves are spread out to dry on enormous ventilated trays. The leaves are then processed and graded, with whole leaves at the top of the scale, and the powdery dust at the bottom.

Tea, while a darn good excuse, isn’t the only reason to journey to Assam. There are a couple of significant Hindu pilgrimage sites here, and one of the top game preserves in the world.

The Kamakhya Devi temple, known for its animal sacrifices, occupies a prominent hilltop in the middle of town. The Umananda Temple, dedicated to Shiva, is the centerpiece of Peacock Island. Hindu priests and golden langur long-tailed monkeys are the only permanent residents of this small bluff in the Brahmaputra River. Ten rupees buys you a round-trip ferry ride from Kachari Ghat, about 20 minutes each way.

The Assam State Museum, located near the Standard Chartered Bank on the GNB Road, provides a good introduction to the history, culture and art of the region. Just looking around, one can see Burmese, Chinese and Indian influences on the people and the culture.

Although there are many stores selling the distinctive champagne-colored Assamese silk, if you travel to Sualkuchi (about 20 miles from Guwahati on the north bank of the Brahmaputra River) you can see the weavers in action.

Don’t miss a trip to Kaziranga National Park, about 135 dusty, bumpy miles by road from Guwahati. India’s first wildlife sanctuary, it was established a century ago by the English viceroy to preserve the then-dwindling population of the one-horned Indian rhinoceros. There are now some 1,500 of the majestic beasts roaming free in the park, protected by 400 staff and 120 anti-poaching camps.

Tigers, sometimes seen on excursions into the park, are considered an especially auspicious omen on one’s visit. It’s an astonishing experience for visitors who can climb aboard elephants for an early morning ride out into the bush in search of wildlife. That’s when I saw my “lucky tigers,” but also lots of swamp deer, hog deer, storks, herons, a group of wild buffalo and, of course, rhinos.

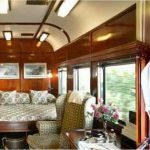

Book it: Boston-based, Audley Travel, which uses “Tailor-Made Journeys for the Discerning Traveler” to describe its business, offers an assortment of tours that take in Assam and offer focus themes on the hardy tea leaf and all that goes into creating the perfect cup.

Contact:

(855) 838-8300

www.audleytravel.com/us/

Similar Stories:

Delaware: Where to Find Easy American Treasure

Brussels, Belgium: Beyond the Chocolate

One Tourist’s View: On Foot in Venice, Italy

Savoring Vienna, One Sip at a Time

Get Social